Some troubledom just figured that if you allow for every codder and shiggy and appleofmyeye a space one foot by two you could stand us all on the six hundred forty square mile surface of the island of Zanzibar.

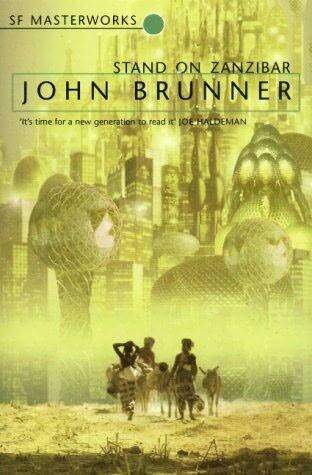

John Brunner is the type of author that you should be careful with. His work could be easily divided into different periods, and not all of those are equally good. However, there is no question of quality when it comes to his cycle of catastrophic SF books. Stand on Zanzibar is a colossal work - both literally, and figuratively. Completely revolutionizing the stylistic conventions of SF, it is one of the most significant pieces of dystopian fiction I've ever read, and a shining example of the many ways New Wave reinvented the genre.

Forty-year old predictions are rarely any good, and when you reach the year of an SF novel's "distant future", it is easy to smirk at the author's naivete. Not so in this case. Even if Brunner's vision did not come entirely true, the patterns he saw decades before mostly anyone else, are undeniable. And we can't really smirk at Stand on Zanzibar without the little nagging feeling that its prediction is just biding its time.

The year is 2010 and the world has gone crazy. Population has long since passed the seven billion mark, and the twenty first century is a whirlwind of hysteria. Computers on the verge of becoming AI take humanity's decisions for it, drugs are legal and used by everyone; politics are done through assassination in the shadows, and scientists burn incense to appease volcanoes. People could turn into mass murderers for no reason whatsoever while simply crossing a street, commercials are all over the place and Mr. and Mrs. Everywhere have your faces and speak with your voices while taking you through your TV to places where you could never go in the real world. And as every advanced country has accepted laws for genetic purity that deny anyone with hereditary diseases the right to reproduce, and tensions between the superpowers constantly escalate into armed conflicts, two small countries focus the world's attention on themselves.

Beninia is a fictional African country that should have been assimilated by its more powerful neighbors, but for some reason hasn't been. And even though it is poor and underdeveloped, there are no internal conflicts there, while the rest of the world devours itself. Meanwhile The Enlightened Democracy of Yatakang (another fictional country, possibly cover for Indonesia) makes a startling announcement - a break-through in genetic engineering that could change the world forever.

The pacing of the story is slow and measured, but the plot is just one of many devices that John Brunner uses to paint the mad reality of a world where people are packed so close to each other that they've reverted to a state of neo-barbarism that I am pretty sure wasn't nearly as plausible in 1968 as it is today. Stand on Zanzibar is as much a warning as it is a prediction, and a disquieting quantity of elements from its monstrous reality are all too easy to recognize in our own. The author has been meticulous with every detail of his world. The book is written in an entirely fictional slang - a mirror of the hysterically fast day-to-day lives of the people in this dark twenty first century. Every other word is a combination of two longer ones. Everything is shortened, simplified, mass-produced, a tool for word-games. "Bastard" is no longer an insult, but "Bleeder" is - there is no greater fear than being found to have a hereditary disease. Drugs are so widely used, that everyone is "out of" or "in orbit", depending on whether some form of communication has been achieved.

The panoramic view of Stand on Zanzibar's world shows us a number of social phenomena. There are the "shiggies" - a class of women that have no home of their own (living space is now the greatest luxury and even the richest could rarely afford an apartment of their own) but change partners and live with them. Tobacco is no longer used, but marihuana is legal and more widely used than tobacco ever has been. But the most frightening example of Brunner's dystopian society are the "muckers". Derived from "amock", the word is used to describe people who couldn't stand the pressure and rhythm of their lives. When they break, they turn into mindless berserkers, killing sometimes scores of people before being killed themselves. Even without the muckers, the world is filled with terrorists and saboteurs, often wreaking havoc and destruction just for the heck of it, as a hobby. Humanity's drive for self-destruction, fueled by something as simple as lack of space, is one of the most powerful points of the book, and one of the most horrifying.

Meanwhile, back at planet Earth, it would no longer be possible to stand everyone on the island of Zanzibar without some of them being over ankles in the sea.

Stand on Zanzibar's most interesting quality, however, is the structure. Its chapters are more or less equally divided between four completely different categories, but mixed together and following no distinguishable order. Each chapter starts with the label of its category and there are four separate contents for each, although reading them separately seems to me to be completely pointless.

continuity is the main story-arc that follows the few "main" characters of the book and the events around the countries of Beninia and Yatakang. Although Brunner isn't overly concerned with character development, the protagonists are still fully developed and believable. The story itself is nothing special and on its own wouldn't merit any attention. Good thing it's not on its own.

context gives us background information on Stand on Zanzibar's world through different means - news snippets, articles, book excerpts or interviews with various people.

tracking with closeups follows little story-lines that have nо influence over the continuity line (although a few tracking characters appear there in minor roles), but give broader view of Brunner's Earth of 2010. Almost none of the lines appear in more than two tracking chapters, and yet characters are just as fleshed-out as those in continuity.

the happening world is possibly the most innovative and atmospheric part of Stand on Zanzibar. It is also the hardest to digest. It follows context's idea, but goes to the extreme. Each happening world chapter is a seemingly random collection of little pieces of commercials, messages, word-games, songs or other symbols of this new world. Brunner plays a lot with rhythm in those parts of the book and combines different snippets in monolithic walls of text, changing the source faster and faster until every word comes from a different place and the reader feels like his or her head is about to explode.

Stand on Zanzibar uses those four drastically different ways to offer its content, but all of them are united under the single purpose of world-building. The effect is so powerful, that at times I wanted to close the book just to catch my breath. The psychic intensity of the novel could actually be partly a weak point. The information overload is intentional, but that doesn't make it any less... well, overloading. This is not a book you read in huge chunks. It is just too intense for that.

That said, Stand on Zanzibar is still extremely engaging. It pulls you in and never lets go, even when you want to take a break from its psychedelic, self-destructing world. True, it is a bit outdated - computers haven't been taking up whole rooms for decades, and we're halfway through 2010 already - but Brunner's tale of an inverted apocalypse is still so shockingly plausible and compelling, so thought-provoking and unsettling in its accuracy, not to mention so darn well written, that it fully deserves a place in SFF's hall of fame.

10/10

Following the most recent mass shooting (San Jose), I was reminded of Brunner's "berserkers". Amazing correlation!

ReplyDeleteAs I absorbed the impact of yet another mindless mass shooting (San Jose), I was reminded of the "berserkers in Brunner's novel, which I read in the 70's. Amazing!

ReplyDelete